In the enchanted world of employee benefits, one question looms large: when it comes to disputes under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), is arbitration the Wizard with all the answers? While ERISA claims are indeed arbitrable as a general matter, a growing number of circuit courts have ruled that arbitration clauses cannot overreach and extinguish substantive remedies. Several plan sponsors have tried to add arbitration clauses that waive plan-wide remedies, but courts have found them to constitute prospective waivers of participants’ statutory rights, rendering them unenforceable under the “effective vindication” doctrine.

Dear Old Federal Arbitration Act

Arbitration clauses are provisions in contracts that require parties to resolve their disputes outside of court, through private arbitration. The Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) was enacted to overcome a perception of judicial hostility towards arbitration agreements and to promote arbitration as a quicker, less expensive method for resolving disputes. Under the FAA, a written agreement to arbitrate “shall be valid, irrevocable, and enforceable, save upon such grounds as exist at law or in equity for the revocation of any contract.” 9 U.S.C. § 2. The FAA is thus “a congressional declaration of a liberal policy favoring arbitration agreements.” Moses H. Cone Memorial Hosp. v. Mercury Constr. Corp., 460 U.S. 1, 24 (1983).

At first glance, then, it would seem an agreement to arbitrate is the end of the yellow brick road. But as any ERISA traveler knows, the path is rarely so simple.

What Is This Effective Vindication Doctrine?

An arbitration clause may be able to dictate the forum and manner in which disputes are resolved, but it cannot “alter or abridge substantive rights.” Viking River Cruises v. Moriana, 596 U.S. 639, 653 (2022). Put another way, an arbitration clause cannot operate as a “prospective waiver of a party’s right to pursue statutory remedies.” American Exp. Co. v. Italian Colors Restaurant, 570 U.S. 228, 235 (2013). This is known as the “effective vindication” doctrine: courts will invalidate arbitration provisions that prevent parties from effectively vindicating their substantive rights or remedies under a statute.

The effective vindication doctrine is often implicated in ERISA cases because some plan sponsors have included mandatory arbitration provisions in their plans to try to avoid class action litigation. However—while courts have agreed that ERISA claims are generally arbitrable—the attempt to avoid class action litigation has not been a magical Oz outcome. The perhaps innocent attempt to waive class remedies has proven to be fraught with problems. See, e.g., Fleming v. Kellogg Co., 2024 WL 4534677, *5-6 (6th Cir. Oct. 21, 2024); Smith v. Board of Directors of Triad Manufacturing, Inc., 13 F.4th 613, 621-22 (7th Cir. 2021).

The key question, then, is whether arbitration provisions that attempt to prevent class actions are impermissible…

Is your company offering an Employee Stock Ownership Plan, or “ESOP”? ESOP stock can be a valuable benefit. But like any investment, it comes with both advantages and potential risks. At first glance, it may seem like there’s no downside to receiving company stock in exchange for years of service. But ESOPs differ from other retirement plans, such as 401(k) plans, which usually offer a diversified menu of investment options; or defined-benefit pensions, where you are guaranteed a fixed monthly retirement check for the rest of your life. ESOP stock carries unique considerations employees should understand. Here are three key points to keep in mind:

- ESOP shares are not “gifts” from your employer.

It’s a common misconception that stock contributions to your ESOP account are simply a gift—something employees should accept without question. In reality, ESOP contributions are a form of compensation, not charity. When your employer contributes stock to your ESOP account, it is doing so in place of other forms of pay or benefits. In fact, your employer receives tax deductions for ESOP contributions precisely because the IRS views ESOP contributions as part of employee compensation.

- Your ESOP investment may carry more risk than other investment options.

ESOPs for non-publicly traded companies invest in private employer stock, which is not traded on an open market. This can create significant investment risk. If a valuation is flawed or the company faces financial trouble, the value of company stock—and therefore the value of your ESOP account—can decrease. On top of that, employees’ livelihoods are already tied to their employer, which means a downturn could hit both your job and your retirement account at once.

- ESOP shares are sometimes overvalued or inflated at the time of contribution.

The value of ESOP shares is determined at the time the ESOP purchases the company and then reassessed annually. But the valuation of private company stock is complex and depends on factors like:

- Whether the ESOP received a controlling interest in the company.

- Whether the shares are marketable (can be sold or liquidated).

- Whether the financial information and projections used to value the company were realistic and unbiased.

For instance, employees may technically “own” 100% of company shares but they often lack key shareholder rights such as electing the board. If a valuation doesn’t properly account for lack of control, limited marketability, or other factors, employees may end up overpaying for company stock. Yet most employees receive little to no information about how these valuations are conducted, leaving uncertainty about whether their retirement savings reflect fair value.

Bottom Line: ESOP stock is not a gift—it is compensation employees earn through years of service with a company. That’s why federal law (ERISA) requires that the stock allocated to your ESOP account was based on fair market value. Both current or former employees (with vested ESOP stock) have the right to ensure their stock was fairly valued during the initial ESOP transaction and to protect themselves from being short-changed on their hard-earned retirement benefits.

Accounting fraud is surprisingly prevalent. Often synonymous with financial fraud — think of Sam Bankman-Fried’s involvement in the collapse of FTX or the demise of Enron in 2001 — recent studies indicate that up to 41% of companies engage in accounting violations each year.

Despite robust regulatory and enforcement programs championed by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), each year accounting fraud results in investor harm, financial losses, and negative market impacts.

Accounting fraud occurs when a company or individual deliberately misrepresents information to gain money or avoid financial loss. Accounting fraud creates a false picture of a company’s health to deceive investors, regulators, and others.

How it happens is more obvious than you’d think.

Spotting the Warning Signs of Accounting Fraud

Red flags that often indicate accounting fraud may be occurring include:

- Significant pressure from supervisors to meet earnings and other performance expectations,

- Supervisory focus on short term performance rather than long term company outlook, for example, pressure to do “whatever it takes” with the numbers to make this quarter look outstanding,

- Financial reporting and accounting infrastructure that lags behind the growth of the company, and

- Management’s poor “tone at the top,” with excessive focus on the firm’s financial performance, to the detriment of quality of work, and employee support and development.

The Most Common Forms of Accounting Fraud

Accounting fraud can take many forms, but most schemes fall into a few well-recognized categories that share a common goal: to distort a company’s true financial picture for personal or corporate gain. These categories include:

- Falsifying revenue, that is, falsifying the financials to make it look like the company earned more than it did,

- Concealing debts or risks that should be included in the financials to make the company look healthier than it is,

- Improper accounting, meaning ignoring accounting rules to boost stock prices, and

- Omitting critical facts or outright lying in SEC filings, earnings calls, or press releases that result in misleading investors or even causing investor harm.

How does this hurt you and me? Lies or omissions affect real people—employees whose retirement savings are tied up in company stock, pension funds investing on behalf of government employees or other public servants, or everyday investors trying to build a future.

The Role of the Whistleblower

Officers, directors, auditors, accountants, vendors, and others with knowledge of accounting fraud can curtail and stamp it out. This is where whistleblowers play a critical role. Tips about accounting violations have not only triggered investigations by the SEC but have also led to substantial whistleblower awards. In cases where the information provided by the whistleblower results in a successful SEC enforcement action and monetary sanctions collected of more than $1 million, the whistleblower can be eligible for an award under the SEC Whistleblower Program. Whistleblowers who possess actual knowledge of the securities fraud and come forward to report that information to the SEC enable the agency to quickly detect and halt accounting fraud.

Importantly, the SEC has stated that accounting fraud cases are a priority for the Division of Enforcement for 2025.

Turning Red Flags into Action

If you work at a company and see signs of accounting fraud, you may be able to help put a stop to it. Whistleblowers are usually insiders who know how the numbers are manipulated or falsified, know who approved the manipulation or falsification, or know how certain risks or liabilities were hidden.

If you see the signs, and you’re ready to act, you should give serious thought to contacting an experienced whistleblower attorney. While you certainly do not need to be an attorney to identify possible accounting fraud at or related to your job, an attorney can help you report your information confidentially, correctly, and carefully. Your voice could be the key to exposing the truth, stopping fraud, and protecting countless others from harm.

Interviewer’s Note: This column about fiduciary issues affecting public pension systems is the general responsibility of Suzanne Dugan, who usually writes the column or invites guests to offer some helpful commentary. Suzanne is the founder and head of the firm’s Ethics and Fiduciary Counseling practice, one of the country’s most active and recognized practices providing trusted counsel to public pension trustees and staff. Suzanne was recently named President of the National Association of Public Pension Attorneys (NAPPA). NAPPA is almost 40 years old and provides an important opportunity for public pension lawyers to come together to learn about the most critical matters affecting their work.

As Suzanne begins her one-year term as President of NAPPA, she thought this a good moment to flip the seats so she can share a little bit about her work on your behalf and as the leader of this group. Since she and I have spent the last couple of decades working on and discussing public pensions, I’ll serve as the foil in this conversation. Hope you enjoy.

Luke Bierman: You’ve been chosen by your peers to lead NAPPA. Tell us a bit about the organization—how you became involved, how it’s organized, and how NAPPA is different from other organizations that work with public pensions.

Suzanne M. Dugan: NAPPA is the only national professional association focused exclusively on public pension attorneys. The beauty of the organization is that it provides an opportunity to exchange information, advance knowledge and education, and foster best principles and sound practices in the field of public employee retirement systems. Public pension plans are a bit unique as they are not governed by ERISA but rather by provisions enacted in their home jurisdictions. These laws might be similar across states and municipalities, allowing members to share their experiences very neatly, but can also vary across the country, giving legal practitioners opportunities to learn about these differences and apply those lessons by analogy. NAPPA’s singular focus on public pensions and its approach of similarity and difference separates it from other organizations.

The organization hosts two educational programs each year. The Winter Seminar devotes a half-day each to NAPPA’s four sections—Benefits, Fiduciary and Plan Governance (my personal favorite), Investments, and Tax—as well as general interest topics on the final morning of the program. The Legal Education Conference, which runs for four days, focuses more about the law and legal issues affecting public pension plans on a wide range of topics and provides public pension attorneys with an opportunity to obtain continuing legal education credit. It is not unusual for several hundred lawyers to attend these programs, which are organized by the four sections I mentioned, as well as our education committees on topics such a cybersecurity and data privacy, funding challenges, public safety, securities litigation, and new member education. NAPPA also publishes a semi-annual newsletter, The NAPPA Report, that allows members to provide articles relevant for their peers in the public pension world.

I began my involvement as a member while working as Special Counsel for Ethics in the Office of the New York State Comptroller in the mid-2000s. After joining Cohen Milstein in 2011, I became involved with the section on Fiduciary and Plan Governance, presenting and organizing programs, and then was asked to assist with the New Member Education Committee. In 2024, I was thrilled when then-NAPPA President Laura Gilson, the General Counsel of the Arkansas Public Employees Retirement System, asked me to serve as Vice President. I’ve been lucky to see NAPPA from the perspectives of both in-house and outside counsel to public pension plans, which I think enhances my capacity to have a positive impact as President.

What really distinguishes NAPPA members is their commitment to the mission. Protecting the retirement security of educators, public safety officers, and other government employees is critically important, especially at a time when it feels as though government employees are under attack. It’s meaningful work for these attorneys, whose efforts benefit millions of retirees and the beneficiaries who depend on public pensions. Indeed, I’m a member of a public pension system after 20 years of public service in New York State, so I fully appreciate how important that pension check is to the beneficiaries of our clients. It’s essential to ensure that those checks get to those who devoted their careers to public service. We’re all proud to play a role in that important work.

LB: I know what you mean: I get one of those checks every month and share your enthusiasm and commitment to the beneficiaries of the public pension systems. To keep up to date with your practice, you recently attended NAPPA’s annual summer conference, which is where you became President. What were the most salient issues on the agenda?

SMD: There are some issues that are perennial, so NAPPA covers them at each meeting–professional ethics, recent litigation, federal legislation, and tax changes, for example. Other topics are more, well, topical—dependent on current trends. For example, cybersecurity and data privacy is top of mind these days, and we had a panel on that topic. I moderated a panel discussing the challenges of public comment periods on Board meeting agendas, and how to craft written policies that satisfy the First Amendment while allowing boards to function efficiently and effectively. We had a very well-received panel with Julie Reiser, co-chair of the firm’s securities practice, discussing the implications for public pension plans wrought

by the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn the Chevron deference doctrine. It was a wide-ranging agenda designed to keep public pension attorneys well informed.

LB: How does your work, and now leadership, at NAPPA complement your practice?

SMD: The best part is getting to know lawyers from around the country doing public pension law. I have learned so much from these people over the years. Of course, as I’ve gotten to know them, I feel comfortable calling them to ask questions, finding out how they approach challenges, learning what is new and coming my way. And I do like to help other attorneys, especially the new generation of lawyers who will be representing public pension systems for decades to come; the trust funds at the heart of the public pension world are not just long-term investors but are essentially perpetual ones, so it is not that hard to imagine that some of these lawyers new to NAPPA will be leaders of NAPPA in 2050. I enjoy that aspect of the organization and I hope that will be a part of the membership initiative I can foster as President.

LB: Thanks, Suzanne, for sharing more about NAPPA. Good luck in leading the organization.

One month after the U.S. Supreme Court hindered judges’ power to universally pause federal policies, hundreds of public interest lawyers took a crash course on using class actions to sue the president.

The June decision in Trump v. CASA had found courts could only grant relief to named parties in a case, but suggested that policies could still be paused on a nationwide basis through class action litigation — a procedurally complex process by which representative plaintiffs can sue on behalf of all similarly situated people.

And so in July, the advocacy group Democracy 2025 held a training for its coalition of more than 500 organizations that call themselves the “united legal frontline” in challenging President Donald Trump’s controversial policies in court.

Joe Sellers of Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll PLLC — who has worked as a class action litigator for four decades and sits on the Judicial Conference of the United States’ Advisory Committee on Civil Rules — led a webinar on Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which governs the class action process.

Sellers says he prepared an hourlong program on class actions after he was told that many policy litigators “know a lot about a lot of areas, but they’re not very familiar with this [type of litigation].” He explained to them the requirements of Rule 23’s various subsections, what the CASA decision did and did not decide, and how to avoid the yearslong delay typical of the class approval process.

“Here, where you’re challenging a discrete governmental action that has an imminent effect on a group of people … the pursuit of class claims can be framed in a way that is very lean,” he told Law360. “You convey to the court an interest in moving as quickly as possible to get a class certified, along with the relief that you’re seeking.”

Class actions involving public policy are nothing new. They hearken to the modern origins of Rule 23 — revisions made in 1966 with the Civil Rights Movement in mind. And even before the CASA opinion altered the litigation landscape, class actions played a growing role in lawsuits seeking to stop Trump’s policies. But now that the high court has pointed to class actions as a vehicle for such claims, the administration might seek new ways to block class certification.

. . .

Class actions do seem like the simplest way to replicate the relief provided by universal injunctions, Sellers said, and “on the face of it, this doesn’t sound like a major change. But class action litigation is itself very significant, protracted and expensive,” he said. “It potentially interposes an initial step in the process of obtaining relief.”

Certification, which is often required to pause federal policies, often takes time and requires discovery. But not always.

On August 28, 2025, the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) issued an Advisory and Financial Trend Analysis on Chinese money laundering networks (CMLNs).

Chinese money laundering networks pose a significant threat to the U.S. financial system. FinCEN’s Financial Trend Analysis highlights the scope and breadth of CMLN activity in the United States. FinCEN analyzed 137,153 Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) required Suspicious Activity Reports filed by financial institutions between January 2020 and December 2024 that described suspected CMLN-related activity, totaling approximately $312 billion in suspicious transactions.

Below are highlights from the reports:

What are CMLNs?

- CMLNs are professional money laundering networks that are based in the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the United States, or other parts of the world. As discussed in the Advisory, CMLNs are often used by Mexico-based cartels to launder drug proceeds into the U.S.

- CMLNs often recruit private individuals who carry passports from the PRC to play a role, wittingly or unwittingly, in these networks to launder money across the globe.

- Chinese citizens’ demand for large quantities of U.S. dollars and cartels’ need to launder illicit U.S. dollar proceeds has resulted in a mutualistic relationship wherein cartels sell off illicitly obtained U.S. dollars to CMLNs who, in turn, sell the U.S. dollars to Chinese citizens seeking to evade China’s currency control laws.

CMLNs May Recruit Employees Inside Financial Institutions.

- CMLNs often utilize trade-based money laundering, money mules, and online mirror transaction methodologies involving fake trading platforms.

- CMLNs may recruit financial institution employees to act as insiders or infiltrate and place CMLN members within a financial institution to assist in money laundering schemes.

- CMLNs may also provide money mules with counterfeit Chinese passports to facilitate account opening and other illicit financial behavior.

CMLNs Favor Real Estate Purchases for Money Laundering.

- As discussed in the Financial Trend Analysis, financial institutions filed 17,389 SARs between 2020 and 2024 associated with more than $53.7 billion in suspicious activity involving the real estate sector.

- CMLNs may use money mules, like Chinese investors, or shell companies to purchase U.S. real estate with laundered funds.

Please read FinCEN’s full Advisory and Financial Trend Analysis for a comprehensive list of red flag indicators.

++++++++++

FinCEN requires financial institutions to file a SAR if it knows, suspects, or has reason to suspect a transaction conducted or attempted by, at, or through the financial institution involves funds derived from illegal activity. A SAR can be accessed through the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) E-Filing System.

If you believe you have witnessed a suspicious activity involving money laundering, we encourage you to contact a Whistleblower lawyer, who focuses on FinCEN-related matters.

About the Author

Christina McGlosson, special counsel in Cohen Milstein’s Whistleblower practice, focuses exclusively on Dodd-Frank Whistleblower representation. She is the former director of the Whistleblower Office in the Division of Enforcement at the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission. She was also a senior attorney in the SEC’s Division of Enforcement, where she assisted in drafting the SEC rules to implement the whistleblower provisions of Dodd-Frank. She also served as Senior Counsel to the SEC’s Director of the Division of Enforcement, and Senior Counsel to the SEC’s Chief Economist.

Christina represents whistleblowers in the presentation and prosecution of fraud claims before the SEC, CFTC, FinCEN-, as part of the U.S. Treasury, the Department of Justice, and other federal government agencies.

Christina McGlosson, Special Counsel: Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Practice

Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll PLLC

1100 New York Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20005

E: cmcglosson@cohenmilstein.com

T. 202-988-3970

Advertising Material. This content is informational in nature and should not be read or interpreted as legal advice. Should you need legal advice, please contact a lawyer.

Expert Analysis by Rebecca Ojserkis

After decades of standard practice, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit each adopted their own new stricter standards to issue notice to collective action opt-in plaintiffs in Swales v. KLLM Transport Services LLC in 2021,[1] and in Clark v. A&L Home Care and Training Center LLC in 2023.[2]

Over the past four years, defendants in other circuits have pushed, without success, for the expansion of these more stringent procedures. As recently as July, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit rebuffed such efforts.[3]

But the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit has now charted an altogether new ground. On Aug. 5, the court issued a ruling in Richards v. Eli Lilly & Co., in which it announced a new approach for district courts to determine whether to issue notice to opt-in plaintiffs.[4]

The contours of the test will only fully take shape as district courts in the Seventh Circuit tackle implementing this new standard.

Notice and Why It Matters

Legislation including the Fair Labor Standards Act, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act and the Equal Pay Act allow workers to litigate their claims together in collective actions.

Specifically, the statutes authorize plaintiffs to bring suit on behalf of “themselves and other employees similarly situated.”[5]

Less than 10 years after its passage, Congress amended the FLSA — in response to the proliferation of union‑initiated suits — to require each similarly situated worker to file a written consent to join the suit.[6]

The statute of limitations on the claims of each worker is not tolled until the court receives their personal consent.[7]

The need to affirmatively opt in distinguishes collective actions from class actions, where all but the named parties can remain absent. The intent of this approach was to create assurances that the workers wanted to be bound by any judgment.[8]

However, in order to submit a written acknowledgment that they want to be part of a representative action — and stop the clock on their claims expiring — workers must know about the action. That is where the question of notice comes in.

Existing Standards to Issue Notice

In 1989, the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed in Hoffmann-La Roche Inc. v. Sperling that trial courts must inevitably get involved in the notice process.[9] While encouraging early intervention, the high court reserved for district judges’ discretion the details of how they would exercise their role.[10]

Since then, the majority of district courts have followed a variation of the Lusardi two-step test, derived from the U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey’s 1987 decision in Lusardi v. Xerox Corp.[11]

Under this approach, courts have issued notice to putative members of the collective early on in the litigation, after only a modest showing that they are similarly situated to the named plaintiffs.

In the past four years, however, the Fifth and Sixth Circuits have erected two new, but different, thresholds to issue notice. The Swales and Clark tests require substantial discovery, and thus time, to meet in order to show that workers are similarly situated by, respectively, a preponderance of the evidence or a strong likelihood.[12]

Earlier this summer in Harrington v. Cracker Barrel Old Country Store Inc., the Ninth Circuit refused to jump on either bandwagon and reiterated its commitment to its two-step precedent.[13]

In 2020, the Seventh Circuit punted on how and when courts should issue notice to opt-in plaintiffs in Bigger v. Facebook Inc.[14] But it has now weighed in.

The Seventh Circuit’s New Guidelines

The underlying suit that led to the Seventh Circuit’s new standard, Richards v. Eli Lilly & Co., involves Age Discrimination in Employment Act claims alleging that the pharmaceutical company overlooked employees who were over the age of 40 in its promotion practices.[15]

The Seventh Circuit accepted an interlocutory appeal from the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana and agreed to provide “clearer guidance” to lower courts on the necessary showing for court-issued notice.[16]

The circuit’s holding, intending to provide a “uniform, workable framework,” outlines a multipart decision tree.[17]

First, plaintiffs must present evidence that there is at least a dispute of material fact as to whether the named and opt-in plaintiffs are similarly situated, i.e., subject to a common policy or practice.[18]

Like Lusardi step one, evidence can come in the form of affidavits and counter‑affidavits.[19] Defendants may put forth rebuttal evidence to which the plaintiffs may then respond.[20]

After a fact dispute is identified, the district court can choose to issue notice, with a decision on certification to come after the completion of the opt-in process and discovery.[21]

Alternatively, the district court can authorize tailored discovery and still require a certification decision prior to notice.[22] Prenotice discovery could be limited to only part of the similarly situated analysis, or it could be more encompassing and overlap with merits issues.[23]

In short, unlike the existing three tests, the Richards standard presents district courts with flexible options on how to proceed.

In setting this new standard and rejecting the three existing ones, the Seventh Circuit invoked three principles that it drew from Hoffmann-La Roche.[24] They are the importance of timely and accurate notice, judicial neutrality, and the use of court discretion to prevent abuses and ensure efficient and proper joinder.[25]

The Implications of Richards

The Seventh Circuit stated that it set out to clarify how district courts should be “assessing the propriety of notice to a proposed collective.”[26] Yet its road map leaves many unanswered questions for district courts to grapple with.

For instance, take the open questions around prenotice discovery. The decision does not restrict the types of discovery authorized. Will document productions require e-discovery? Will depositions take place? If, for example, depositions of a corporate representative or a named plaintiff occur, and the questioning is tailored to the similarly situated topic, can these parties be deposed on other merits issues in a second sitting?[27]

Relatedly, the court does not specify how long the discovery and briefing on certification should take, except to discourage unnecessary delay.[28] What does this process of unknown length mean for workers’ running statute of limitations? The Seventh Circuit encourages, but does not require, equitable tolling during this period.[29]

In Clark, two judges on the Sixth Circuit panel gave a similar nudge to district courts,[30] which took the hint and now regularly equitably toll opt-in plaintiffs’ claims.[31] Will district courts in the Seventh Circuit take a similar tack?

Likewise, in Richards, the Seventh Circuit offered that a district court could dismiss a motion for notice without prejudice, subject to reconsideration with later acquired evidence.[32] Will courts embrace this invited flexibility?

Practically, it remains anyone’s guess how this new standard will play out. Will courts’ implementation of Richards operate more like the later notice of Swales and Clark, or will it bear more resemblance to Lusardi? Will employers still stipulate, as some did, to sending early notice? If so, will courts allow, and abide by, such agreement?

Finally, the panel did not speak in unison with respect to which party has the burden of moving for certification or what the burden of persuasion is.

The opinion was authored by U.S. Circuit Judge Thomas Kirsch and joined in full by U.S. Circuit Judge John Lee, who said in passing that they “presume that plaintiffs must establish their similarity at the certification stage by a preponderance of the evidence.”[33]

But in a separate concurrence, U.S. Circuit Judge David Hamilton criticized this discussion as substantively incorrect and beyond the scope of the question presented.[34] So, will district courts take the majority’s language as binding authority or merely influential dicta?

In the months and years to come, parties and district courts will wrestle with these and more questions about how to implement this notice standard in collective actions. But they should not anticipate further guidance from the Seventh Circuit, as it warned that it will not involve itself in a slew of interlocutory appeals to hash out every detail.[35]

The Supreme Court, however, may have more to say. Following the Ninth Circuit’s two-step embrace, Cracker Barrel has sought and received a stay of the Harrington decision while it petitions for writ of certiorari. The Seventh Circuit granted Eli Lilly’s motion seeking the same.[36]

Conclusion

Workers and employers should keep a close watch on whether this now four-way circuit split attracts the highest level of review.

In the meantime, workers and employers should embrace that the question of notice will be tailored to the nuanced facts of each case in the Seventh Circuit. Depending on what makes plaintiffs similarly situated from case to case, they may need to prepare for early discovery or an early opt-in process.

One-size-fits-all is no longer the norm within the Seventh Circuit.

Cohen Milstein’s nationally recognized antitrust practice group recently secured a $375 million antitrust settlement benefiting more than a thousand mixed martial arts fighters who had accused promoter Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) of unlawfully achieving market dominance that locked them into unfair, low-paying contracts.

U.S. District Judge Richard F. Boulware granted final approval to the deal on February 6, 2025, six months after saying he wanted a deal that would return “life changing” money to the Plaintiffs. Litigated over more than a decade, the antitrust class action showcases Cohen Milstein’s ability to achieve justice for its clients by outmaneuvering and outlasting deep-pocketed corporate defendants.

The settlement in Le, et al. v. Zuffa LLC (dba UFC), et al., 15-cv[1]01045-RFB-BNW (D. Nev.), covers more than 1,100 fighters who competed in UFC-promoted MMA bouts taking place or broadcast in the United States from December 16, 2010 to June 30, 2017.

Comparing their victory to “the end of a very, very long fight count,” Nate Quarry, one of the six original Le plaintiffs, told an interviewer that he and other plaintiffs broke into applause when the judge announced his approval. “Knowing that we get to split hundreds of millions of dollars between over eleven hundred fighters, that is an amazing feeling,” he said.

Under the settlement, Plaintiffs’ attorneys said 35 fighters should receive more than $1 million, about 100 fighters will get more than $500,000, and most of the remaining fighters in the class will be allocated amounts of between approximately $50,000 and $250,000. According to the Plan of Allocation, the minimum individual recovery is $15,000.

Fighters who have participated in UFC bouts since July 1, 2017 continue to litigate a second antitrust class action, Kajan Johnson, et al. v. Zuffa, LLC, which was filed in 2021 by Cohen Milstein and its fellow co-lead counsel.

Quarry, who has been vocal about the physical and financial toll caused by his championship MMA fighting career, said he and other Plaintiffs will continue the legal fight until the rules are changed for current and future MMA fighters. “… [O]ur goal from the very beginning was to hopefully get some monetary relief for the fighters that had been just horribly shortchanged. But then also we wanted to change the sport,” he said.

In certifying the Le class in 2023, Judge Boulware said plaintiffs had established that UFC parent company Zuffa had “willfully engaged in anticompetitive conduct to maintain or increase their market power.”

“Due to this anticompetitive, coercive conduct, fighters were trapped by Zuffa’s exclusionary contracts and their restrictive terms, creating a situation in which Zuffa had unfettered power and opportunity to suppress fighters’ compensation,” the judge wrote..

Dating from at least 2010, Plaintiffs alleged that UFC’s anticompetitive behavior allowed it to retain more than 80% of all revenue generated by MMA events in the U.S., while paying UFC fighters a fraction of what they would earn in a competitive marketplace. That percentage remained unchanged despite the explosive growth of Zuffa, which promoter Dana White and brothers Lorenzo and Frank Fertitta purchased for $2 million in 2001 and sold 15 years later for roughly $4 billion.

According to Judge Boulware, Plaintiffs established that UFC achieved its market power through anticompetitive means like buying and shutting down rival companies and “locking up” fighters into unfavorable and exclusionary three- or four-bout contracts. Fighters had no ability to negotiate terms, since UFC was effectively their only potential employer. And while UFC could drop fighters without explanation, the contracts barred the fighters from going elsewhere.

Moreover, UFC strong-armed fighters into signing new contracts before the old ones expired through its power to match them with unfavorable opponents in their remaining bouts, making the contracts “effectively perpetual,” the judge said.

As Nate Quarry put it in a 2024 interview: “They just get blacklisted, they get cut. They get put on the undercard. They are given opponents that aren’t going to be a good match up for them … The UFC is very vindictive. You’re either with the company or you’re against it.”

Even the largest and longest-running frauds can be brought to a screeching halt by a single person who uncovers the scheme and reports it to the government. In recognition of the critical role played by whistleblowers, a number of programs have been established to provide them with substantial financial awards if their information leads the government to recover money from the wrongdoers.

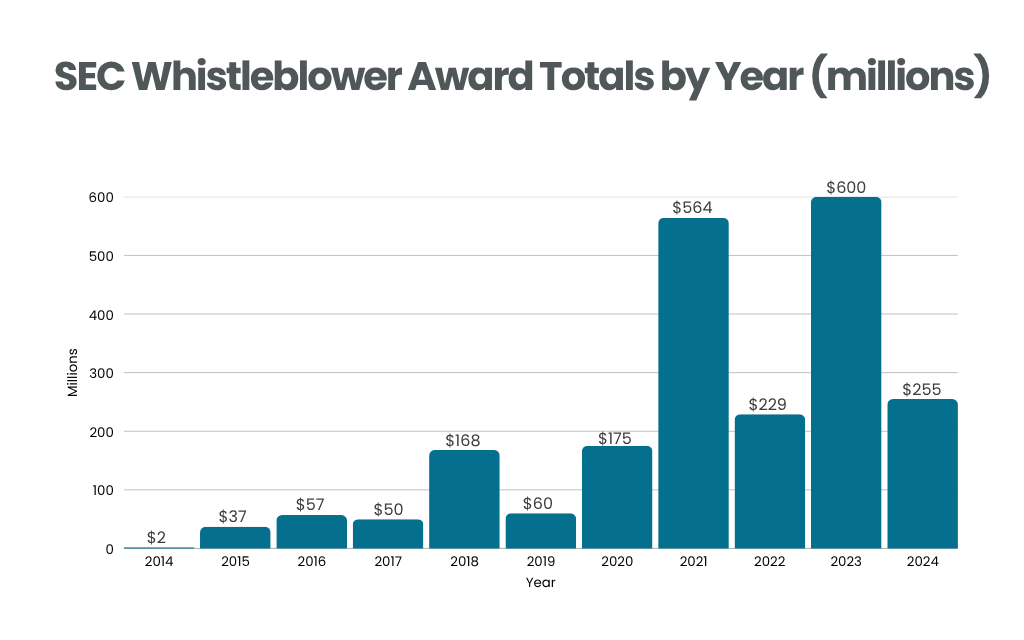

One example is the Securities and Exchange Commission Whistleblower Program. It was established after the Financial Crisis of 2008 and incentivizes whistleblowers to come forward by offering financial awards generally equal to 10-30% of the amounts that the SEC recovers based on the whistleblower’s information. These awards can be substantial. As shown in the graph below, there has been a broad upswing in the amounts of awards paid to whistleblowers by the SEC, punctuated by some extraordinary years that included particularly large awards.

Three Things to Know About the SEC Whistleblower Program

- The identity of whistleblowers is treated as confidential by the SEC. The SEC will take all reasonable steps to preserve whistleblower confidentiality and does not disclose publicly the identity of whistleblowers even at the end of a case when an award is made. In fact, whistleblowers who are represented by counsel are allowed to submit their information to the SEC without revealing their identity even to the SEC, unless and until the whistleblower applies for an award.

- There are many procedural rules that whistleblowers must follow in order to be eligible for an award, including rules about who can be a whistleblower, when their information must be reported, in what form, and the types of information that qualify for an award. There are also rules that concern how whistleblowers can make an application for an award if a recovery is obtained by the SEC, and the factors that will be considered in determining the amount of an award.

- While a whistleblower must provide information to the SEC that it is not already aware of to qualify for an award, there is no requirement that a whistleblower be a corporate insider. Indeed, many successful SEC whistleblowers are not insiders – they may be industry professionals who came upon evidence of fraud or other securities law violations in the course of their work, or who investigated a company and discovered those violations.

Navigating the Whistleblower Process: Don’t Go It Alone

Individuals who have information about fraud and who wish to participate in a whistleblower award program should retain experienced whistleblower counsel to advise them throughout the process on how to:

- Gather the supporting evidence

- Submit their information to the government in a comprehensive and persuasive manner

- Comply with all procedural requirements to be entitled to an award

- Work productively with the government to assist and facilitate their investigation and enforcement efforts

- Apply for and obtain the highest possible award if the government obtains a recovery

Make Your Information Count

The decision to blow the whistle can be one of the most impactful actions an individual can take to expose fraud, protect investors, and uphold the integrity of our markets. The SEC Whistleblower Program and others like it offer meaningful awards for those who come forward with original, credible information.

If you believe you’ve uncovered fraud, your next step matters. The path to a successful whistleblower award is complex, but you don’t have to navigate it alone. Our team has the experience to help you build a powerful submission, safeguard your interests, and pursue the award you deserve.

Remember, one person can put a stop to fraud.

A federal judge in Colorado has granted preliminary approval of a $27 million settlement in a securities lawsuit brought against InnovAge Holding Corp. by Cohen Milstein on behalf of its clients the El Paso Firemen & Policemen’s Pension Fund, the San Antonio Fire & Police Pension Fund, and the Indiana Public Retirement System.

The settlement would end three years of hard-fought litigation against multiple defendants: InnovAge, a healthcare provider specializing in senior care; certain of its former executives; private equity firms— Apax Partners and Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe—who owned controlling stakes in InnovAge; and underwriters of InnovAge’s initial public offering.

Lead Plaintiffs alleged that Defendants made false and misleading statements regarding InnovAge’s regulatory compliance, the quality of its care model, and the viability of its growth strategy. Government audits uncovered significant compliance violations, including woefully understaffed care centers. The sanctions that followed, including an enrollment freeze, hindered InnovAge’s ability to grow and caused the stock price to plummet, according to Lead Plaintiffs’ complaint.

“When private equity pushes for profits in the healthcare space, it raises risks for patients and shareholders alike,” said Molly Bowen, a partner on Cohen Milstein’s InnovAge team. “By fighting for and obtaining this excellent result, our clients showed how engaged pension funds can hold public companies accountable for fraud and benefit their fellow investors.”

The three Lead Plaintiffs and Lead Counsel Cohen Milstein conducted extensive discovery and motions practice that provided ample evidence about the strengths and risks of the case. Lead Plaintiffs investigated, drafted, and filed a detailed amended complaint and defeated, in large part, Defendants’ repeated motions to dismiss. They engaged in substantial fact discovery, including exchange of document requests and interrogatories, production of hundreds of thousands of pages of documents, serving subpoenas on third parties, and conducting Rule 30(b)(6) depositions of the Lead Plaintiffs and their three investment managers—a total of eight individuals representing six different entities. Lead Plaintiffs also successfully moved for class certification, supported by an expert report on market efficiency and damages.

The $27 million settlement is a class-wide recovery that exceeds the typical recovery in securities class actions, particularly for a case where most damages stem from claims arising under a company’s statements in connection with an initial public offering.

The result is even more remarkable considering the particular challenges presented by InnovAge’s precarious financial state. In virtually all cases, extending litigation for years—through additional dispositive motions, trial, and appeals—carries a risk that the class might recover less (or even nothing). Here, InnovAge’s limited insurance and a significant decline in its stock price during the litigation heightened that risk. During the litigation, InnovAge’s stock price fell from around $6.50 per share to as low as $2.75 per share, raising a risk that the company would have difficulty funding a settlement.

On June 17, 2025, US District Judge William J. Martinez granted preliminary approval of the settlement in the case, which is captioned El Paso Firemen & Policemen’s Pension Fund v. InnovAge Holding Corp. (21-cv-02270-WJM-SBP (D. Colo.).

In the coming months, Cohen Milstein will work with the court-approved claims administrator to oversee the process of disseminating notice of the settlement. Impacted investors can find more information at https://www.strategicclaims.net/innovage/. Judge Martinez scheduled a final approval hearing for November 26, 2025.